Education Inequalities: The State of Play

In this post I want to outline some emerging conversations about education and schooling inequalities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. The experiences of young people and teachers have been captured in a number of discussions about the impact of COVID-19 on education, learning and social inequality. I would like to point out some problematic voices that have tended to speak for, and about those who face the opportunities and the burdens of this disruption, when crisis is never shared evenly. Some of those voices have assured us that in the aftermath of COVID-19, students, teachers and schools need to adopt a ‘business-as-usual’ approach, despite the ways in which this crisis has magnified systemic and structural inequalities. I am interested here in the South West Region of Victoria, Australia – the deindustrialising city of Geelong and its surrounds.

At Deakin University’s School of Education Eve Mayes, Amanda Keddie, Julianne Moss, Shaun Rawolle, Louise Paatsch and Merinda Kelly (2019) are investigating how human and more-than-human relations shape understandings of education inequalities in the Greater Geelong region. In their article Rethinking inequalities between deindustrialisation, schools and educational research in Geelong, Mayes et al. (2018) argue that inequalities are materially generated and perpetuated by human and more than human relations concerned with deindustrialisation and schooling. Mayes et al (2018, p.391):

‘Geelong, and particularly the suburbs of northern Geelong, is a community where independent schools identified as ‘elite’, and schools identified as serving ‘low socioeconomic’ assemble side-by-side. Within an approximate 5-kilometre radius in the northern suburbs of Geelong sits one of Australia’s most expensive elite independent schools, other elite independent schools and public school campuses where children of families most dramatically impacted by the vicissitudes of deindustrialisation go to school. Within this radius are dis-used industrial sites, as well as gentrified conversions of former mills (into boutique antique shops, cafes and restaurants). The majority of Geelong’s services for new migrants and refugees are situated in these northern suburbs; new migrant communities are strongly represented in local demographics, including recently resettled refugees from Burma, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.’

‘Gaps’ such as these are echoed in a United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, UNICEF Office of Research report entitled ‘An Unfair Start: Inequality in Children’s Education in Rich Countries’ (2018) which illustrates that Australia’s education system is nearly the most unequal in the developed world based on education outcomes. One post from ‘Save Our Schools’ addressing this UNICEF report (November 2018, n.p) states that:

‘The UNICEF report cites Australia as one of the most unequal education systems amongst 39 developed countries [p. 10]. In fact, Australia is the equal 2nd most unequal education system with Slovakia and only marginally behind New Zealand on a combined ranking of education inequality across pre-school, primary and secondary schooling. Australia is ranked 36th out of 41 countries in inequality in pre-school attendance, 25th out of 29 countries in inequality in primary school reading achievement and 30th out of 38 countries in inequality in secondary school reading achievement.’

A variety of policy responses aimed at education and schooling inequalities in times of crisis have tended to look to education outcomes as a key indicator of need for intervention. Mayes (2018, p.394) et al. have argued the limits of these ways of understanding inequalities:

‘measurements of (in)equalities between students and schools have become closely related to measures of academic performance. Such measures are assumed to correspond to a ‘reality’ of a gap—assuming pre-established conditions and ontological constants. Even as a familiar theme within Western policy discourses has been to ‘close the gap’ in educational outcomes between disadvantaged students and their more advantaged peers, ‘closing the gap’ rhetoric is closely entwined with the logic that more testing and public access to school data (including test results) will engender more equitable outcomes for marginalised students.’

The definition and measurement of education inequalities through NAPLAN and PISA student testing, and MySchools and OECD local and global ranking of school and student performance, are key parts of Australia’s present education machinery, and indicators of national productivity and growth. In ‘A carpet loom and matters of inequality: an agential realist approach to deindustrialisation and schooling in the City of Geelong, Australia’ Mayes et al. (2020, p.2) describe how policy responses to inequalities in education outcomes have tended to focus on problems of:

‘teacher ‘quality’, the testing of literacy and numeracy, and school accountability as mechanisms to address inequality, while bracketing out significant ontological questions relating to how inequalities are apprehended, ‘measured’ and re/produced’

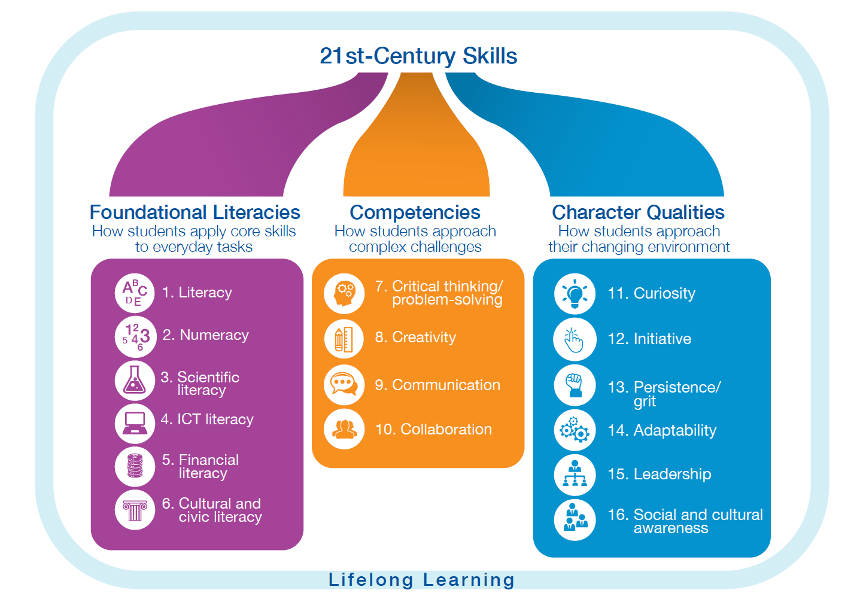

In addition, assemblages such as 21st century skills (World Economic Forum), transformative competencies (OECD) and general capabilities (ACARA) have gained authority and momentum in education discourses over the past 30 or so years as representations of the kinds of human capital – the social and emotional skills, character traits and competencies – that young people are increasingly required to develop in order to thrive. See below for the World Economic Forum’s representation of the skills that individuals require for 21st century education, work and life.

These models, and others like them, are familiar to many of us that work in TAFE’s, schools, and Universities. The question we raise here, and in earlier blogs is how – with predictions of the most catastrophic economic downturn since the Great Depression (A ‘Greater Depression’), and vast social consequences such as rapidly rising youth unemployment – do these problems enable us to navigate the challenges of the current COVID-19, economic, and ecological crisis. Particularly for those young people who are most vulnerable to exclusion?

COVID-19: Education, Social inequality and Exclusion

On April 17th 2020, ABC News published an article Does missing a term due to COVID-19 really matter? What happened to student results after the Christchurch quake which included an interview with one of Australia’s most influential educationalists, Professor John Hattie. Hattie ‘weighs in’ on the possible consequences of school closures in Australia due to COVID-19 and draws comparisons with the Christchurch (NZ) earthquakes in 2011 where ‘the students’ performance actually went up in the final exams’. Also, following Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans (US) in 2005 where after seven weeks of school closures, students ‘recovered quickly and actually began to see gains in test scores’.

The article goes on to provide detail of a family that removed their children from school for an experience of ‘organic learning’ whilst travelling around Australia:

‘Parents who have taken their children out of school for months to travel Australia, like Sharon and Adam Galway, have also found their children were not worse off from an extended gap from the classroom. The Galway’s focussed on organic learning and spending time together as a family instead of text books during their eight-month trip with their children, then aged between four and 12. Two years on, and their children are engaged at school and performing better than most of their peers.’

Hattie argues that with 10 weeks of the school year removed, Australian students would still be getting more time in class than students of other OECD nations such as Sweden, Finland and Estonia. The article ends with Hattie reassuring that education and schooling will soon return to business-as-usual, and that teacher and public ‘stress’ is an indicator of effective transition to new ways of learning:

‘”You have to be amazed what teachers have done to turn the whole system around so that kids can work at home doing various things,” he said.

“But my message is ‘let’s not get stressed about it’.

“When we get back to the old normal the recovery will be reasonably quick.”’

The perceived consequences of COVID-19 for education and learning are understood here in terms of online and at-home learning, school closures, and their impact on student outcomes. But there are many elements missing from this story – notably the digital infrastructure required to support these ways of doing education (assuming that this was just a technical problem) impacting school participation and engagement.

Digital Disruption and Digital Infrastructure: Schools in the Geelong Region

The challenges of the ‘digital divide’ during COVID-19 have been described by the Mitchell Institute in COVID-19 school closures will increase inequality unless urgent action closes the digital divide:

‘While only 3 per cent of high-income households don’t have access to the internet, this increases to 33 per cent among the lowest income households and presents a major barrier and risk for children who are learning remotely.’

‘The gap between the wealthiest households and the most disadvantaged is stark. More than four million Australians access the internet solely through a mobile connection. Families with children under 15 have an average of 2.1 laptops or desktop computers at home, but this drops to 1.4 devices for families in the lowest income bracket.’

Shifts to school-based and distance / online learning during the COVID-19 crisis have raised questions of both home, and school digital infrastructure. In the Geelong region, ‘G21’, a Geelong regional leadership body, in particular the ‘Education Pillar’, have for many years been fighting to gain government funding (to the sum of $8 million) for technical infrastructure that would see a number of under-resourced public schools in the region gain access to suitable internet speeds. In short, Internet bandwidth speeds are unfairly distributed across the Geelong region. The G21 Education Pillar have commented on the issue that is now considered an urgent priority:

‘Most private secondary schools in the G21 region have themselves funded access for their students and teachers to AARNet. This is unintentionally creating a divide between public and private secondary schools within our region.

‘At least seven private schools are benefiting from subscriptions to the super-fast high-capacity AARNet internet, while just one public secondary school has been able to afford to do so. Twenty public secondary schools in the region can’t afford to connect.’

“NBN download speeds range from 12mb to 100mb per second while AARNET download speeds range from 1Gb to 100 Gb per second.”

“It’s like comparing the speed of a snail … to a Ferrari.”

Social inequalities, particularly in the Geelong region, have been understood (pre and during COVID-19) in a number of ways. Internationally recognised educationalists such as John Hattie emphasise the potentially limited consequences of these challenges for particular students in terms of student outcomes, and the opportunity for at-home and online learning experiences among middle-class families. Hattie’s influential research of evidence-based learning outcomes (1,500 meta-analyses of approximately 300 million students) does address the impact of technology, and equity on learning. However, the unequal distribution of technological infrastructure to homes and schools across the region of Geelong and elsewhere are now magnified amidst the COVID-19 crisis. This emphasis on student, teacher and school performance measurement and outcomes can be understood to evade conversations like the ‘digital divide’ in Geelong – and for understanding relations between social inequality, exclusion and education.

2 replies on “COVID-19 and Education Inequalities in Regional Victoria: Beyond ‘Business-as-usual’ Education Futures”

Very interesting read – thank you

LikeLike

Insightful to the emerging situation of unequal learning opportunities amid COVID19.

LikeLike